Mental health issues. It might not seem like a wildly sensational topic but cinema has been finely honing it into one for decades. In fact, a half decent portrayal of something vaguely resembling a legitimate mental health issue will probably earn you at least a nomination, come awards season. Who cares if there is a little embellishment as to what the actual illness looks like? What harm can it do?

Mental health issues. It might not seem like a wildly sensational topic but cinema has been finely honing it into one for decades. In fact, a half decent portrayal of something vaguely resembling a legitimate mental health issue will probably earn you at least a nomination, come awards season. Who cares if there is a little embellishment as to what the actual illness looks like? What harm can it do?

Actually, a lot. One of the major stigmas surrounding mental health issues is that – no matter what particular “name” your issue has – you are worried that your friends and family will think you are crazy. Or that you spend all day crying, cutting off chunks of your hair. And where on earth would they get that perception from? Why, cinema, of course …

Now, I realise that cinema is not solely to blame with our perceptions of mental health issues. Every time there is a mass shooting or attack, I hope and pray that the journalists reporting on the scene don’t seize upon the fact that the assailant was a “loner”, a “weirdo” or on the autistic spectrum. You can either count cards a la Rain Man or you like to commit atrocities. There seems to be no in between for people with ASD and how does that help you assimilate into society?

But cinema is shaping our ideas as to what it looks like to have – and live with – a mental health issue. And that’s where I object to having them used as a plot device that can be neatly wrapped up with a new love interest or some travelling. Not everyone with a mental health issue is suicidal; not everyone hears voices in their head; not everyone is confined to a padded cell. And yet, those are the examples we have.

Most of us, actually, just live with what’s going on inside our heads. Having a mental health issue is the least cinematic thing of all. There will be good days and bad, but you’ll probably keep turning up at work and do whatever you can to allow yourself to cope.

Most of us, actually, just live with what’s going on inside our heads. Having a mental health issue is the least cinematic thing of all. There will be good days and bad, but you’ll probably keep turning up at work and do whatever you can to allow yourself to cope.

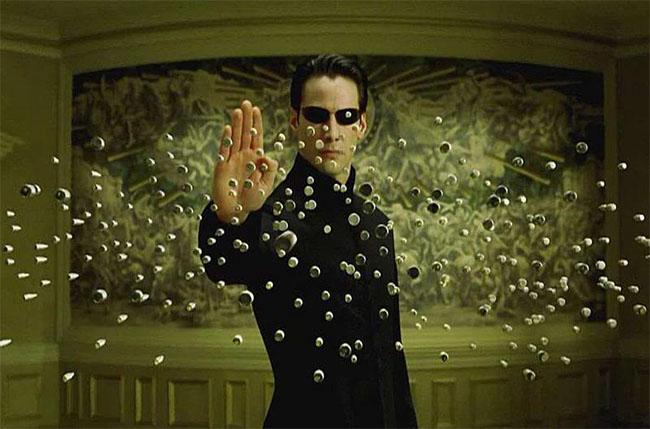

But – to look at cinema – you’d think we couldn’t wait to commit mass murder or speak to the giant rabbit friend we’ve acquired. Especially since mental health issues are often a trope of the horror genre. It’s hard enough to open up about these problems without worrying about what someone else’s opinion might be, based on the media they may or may not have consumed.

And that’s not to say that films such as A Beautiful Mind, Fatal Attraction or One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest are bad films – because they are absolutely not – they’re just completely insensitive about their subject matter. They are a dramatised, made-for-cinema version of mental health in a similar vein to Dustin Hoffman’s autistic savant.

That being said, for those of us with mental health issues, cinema can be the greatest and most life-affirming source of escapism. It can be cathartic to let the tears pour down your face or watch things get blown up. It is sweet relief to drink in that popcorn smell and sit in the dark for a few hours, not having to think about anything other than what is unfolding in front of you.

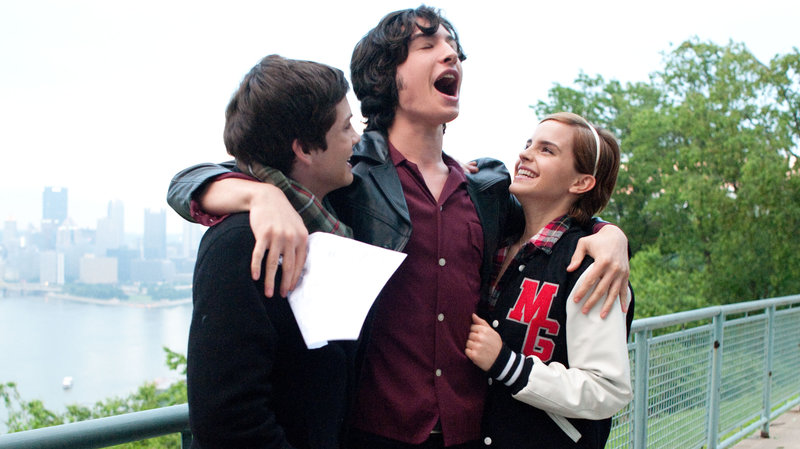

And there are some examples where cinema gets the portrayal of mental health issues really right: The Perks of Being a Wallflower, Silver Linings Playbook and Girl, Interrupted being the most obvious examples. I’m willing to suggest that It’s A Wonderful Life also belongs in that category, albeit it’s slightly more twee.

And there are some examples where cinema gets the portrayal of mental health issues really right: The Perks of Being a Wallflower, Silver Linings Playbook and Girl, Interrupted being the most obvious examples. I’m willing to suggest that It’s A Wonderful Life also belongs in that category, albeit it’s slightly more twee.

The very nature of cinema demands certain things, the most pressing of which is a well-rounded conclusion. Closure. The end. But, for people with mental health issues, we don’t get to skip to the end credits and make everything okay.

However, normalising conversations about what our mental health means to us and having realistic examples in the media will go a long way towards helping.

- Glasgow Film Festival 2025 Announces Country Focus, Special Events and UK Wide Screenings - December 11, 2024

- Armand – Review - November 4, 2024

- Eephus – Review - November 3, 2024